|

Sir

Ernest Shackleton's Endurance

Sir

Ernest Henry Shackleton CVO, RNR (February 15, 1874

– January 5, 1922) was an Anglo-Irish explorer, now

chiefly remembered for his Antarctic expedition of

1914–1916 in the ship Endurance.

After

Captain

Scott died during an attempt to reach the South Pole

in 1912, Shackleton (1874–1922) chose to tackle the

challenge of Antarctica in a different way. He decided

he would attempt to journey across the icy continent

from one side to the other via the South

Pole.

Shackleton was a romantic adventurer, who became

interested in exploration and joined the Royal

Geographical Society while still at sea. In 1901 he got

a place on Captain Scott's first Antarctic expedition,

in the Discovery, through his seafaring skills

and contact with one of the expedition sponsors.

In

1907, he led his own British Antarctic Expedition in the

Nimrod. Other members of the expedition climbed

Mount Erebus and reached the south magnetic pole. Using

ponies and also dragging his own sledges Shackleton

himself led a party which reached to only 97 miles from

the Pole. Although there had not been much government

support beforehand, Shackleton received a hero's welcome

when he returned. He was knighted, becoming Sir Ernest

Shackleton.

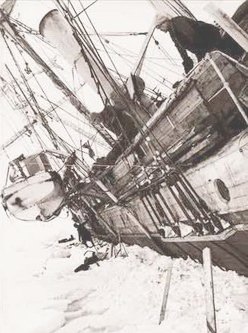

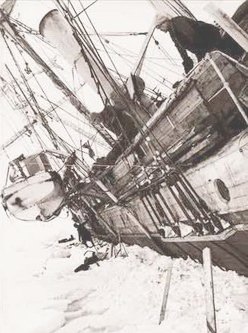

Stuck

in the ice, Antarctic surveyor Frank Worsley and Ernest Shackleton

ABOUT

ANTARCTICA

Antarctica is an enormous continent. More than 99% of it

is covered by ice. In places, this ice is more than

three miles thick. Antarctica is completely surrounded

by the vast Southern

Ocean, half of which freezes in

winter. It is high, windy and extremely cold. There is

no indigenous human population and no life forms at all

except around the coast

More

than 2000 years ago, Greek writers described a large

mass of land in the south of the world. Even though they

had never seen it, they believed it must exist so that

it could 'balance' the land they knew about in the

northern half of the world. They named this imagined

land 'Anti-Arkitos', meaning the 'opposite of the

Arctic'.

Did explorers before Shackleton try to reach the

Antarctic?

Yes. For instance, Captain Cook had tried to

find the great southern continent on his second Pacific

voyage of 1772–74. In 1912, an expedition led by

Captain Robert Falcon Scott had been narrowly beaten in

the race to be first to the South Pole by the Norwegian

explorer Roald Amundsen.

BIOGRAPHY

Shackleton

was born in Kilkee, County Clare, Ireland in 1874, and

served as a merchant marine officer. He went to school

at Dulwich College from 1887 to 1890. In 1904 he married

Emily Dorman. They had three children - Raymond, Cecily

and Edward (Eddie), born in 1911. Their marriage was

marred by numerous affairs on Ernest's part, most

notably his relationship with the American born actress

Rosalind Chetwynd (Rosa Lynd) which was begun in 1910

and continued on and off until his death in 1922.

ANTARCTIC

EXPEDITIONS

1901

National Antarctic Expedition

Shackleton

participated in the National Antarctic Expedition, which

was organized by the Royal Geographical Society in 1901,

and led by Robert Falcon Scott. This expedition is also

called the "Discovery Expedition", as its ship

was called Discovery. The expedition was the

first to penetrate the Ross Sea and reach the Ross Ice

Shelf. He may have placed what has become one of the

world's most famous advertisements in the Times of

London in December 1901: "Men wanted for

hazardous journey. Small wages. Bitter cold. Long months

of complete darkness. Constant danger. Safe return

doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success."

(Some historians have claimed that this ad was placed,

although they do not all agree on when or which

newspaper, but no one has yet been able to locate the

original newspaper clipping.)

1902

attempt on the South Pole

Shackleton

with Scott and Dr Edward Wilson trekked south towards

the South Pole in 1902. The journey proceeded under

difficult conditions, partially the result of their own

inexperience with the Antarctic environment, poor

choices and preparation and the pervading assumption

that all obstacles could be overcome with personal

fortitude. They used dogs, but failed to understand how

to handle them. As with most of the early British

expeditions, food was foolishly in short supply; the

personnel on long treks were usually underfed by any

sensible measure and were essentially starving. Scott,

Wilson and Shackleton made their "furthest

south" of 82°17'S on December 31, 1902. They were

463 nautical miles (857 km) from the Pole. Shackleton

developed scurvy on the return trip and Dr. Wilson

suffered from snow blindness at intervals.

When

Morning relieved the expedition in early 1903,

Scott had Shackleton returned to England, though he had

nearly fully recovered. There is some suggestion that

Scott disliked Shackleton's popularity in the expedition

and used his health as an excuse to remove him; he was

Merchant Marine and Scott was Royal Navy - which was

also part of the contention with whether Albert Armitage

was to remain for the second winter. In part, Scott

exhibited unusual stamina and may not have recognized

differing abilities of others.

Endurance

being crushed by the ice, and sinking

1907–1909

British Antarctic Expedition

Shackleton

organized and led the "British Antarctic

Expedition" (1907–1909) to Antarctica. The

primary and stated goal was to reach the South Pole. The

expedition is also called the Nimrod Expedition after

its ship, and the "Farthest South" expedition.

Shackleton's base camp was built on Ross Island at Cape

Royds, approximately 20 miles (40 km) north of the

Scott's Hut of the 1901–1904 expedition; the hut built

at this camp in 1908 is on the list of the World

Monuments Watch's 100 most endangered sites.

Because of poor success with dogs during Scott's

1901–1904 expedition, Shackleton used Manchurian

ponies for transport, which did not prove successful.

Accomplishments

of the expedition included the first ascent of Mount

Erebus, the active volcano of Ross Island; the location

of the Magnetic South Pole by Douglas Mawson, Edgeworth

David and MacKay (January 16, 1909); and locating the

Beardmore Glacier passage. Shackleton, with Wild,

Marshall, and Adams, reached 88°23'S: a point only 180

km (97 nautical miles) from the South Pole. While the

expedition did not make it to the pole, nonetheless,

Shackleton, Adams, Marshall, and Wild were the first

humans to not only cross the Trans-Antarctic mountain

range, but also the first humans to set foot on the

South Polar Plateau.

Shackleton

returned to the United Kingdom a hero and was

immediately knighted. For three years he was able to

bask in the glory of being "the man who reached

furthest to the south." Of his failure to reach the

South Pole, Shackleton remarked: "Better a live

donkey than a dead lion." It should, however,

be pointed out that Shackleton and his group were

exceedingly fortunate to return from the Pole. They had

cut rations severely, such that there was no margin of

safety. They had very good weather throughout their

return, in contrast to Scott's experience three years

later.

Ernest

Shackleton's hut Antarctica - endangered monument

Sir

Ernest Shackleton’s Expedition Hut - Cape Royds, Ross Island, Antarctica

Built in 1908, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Hut at Cape

Royds is one of six wooden building ensembles remaining

on Earth’s southernmost continent from the heroic age

of Antarctic exploration. Used as an expedition base and

laboratory for scientific research, the building was

designed to withstand extreme weather conditions.

A century of Antarctic blizzards later, the hut is in

surprisingly good condition, but it has begun to suffer

the ravages of time and increased human visitation, and

is in need of urgent conservation. Shortly before the

site’s placement on WMF’s 2004 list of 100 Most

Endangered Sites, the New Zealand-based Antarctic

Heritage Trust had completed a comprehensive

conservation masterplan for the building and the

artifacts associated with it that includes measures

needed to maintain the site, which would take an

estimated five years and $3.8 million to implement.

Since listing, the hut has attracted increased media

visibility and has accrued grants totaling more than

$350,000 toward its preservation. Efforts to remediate

the immediate threat posed by decaying stores left

outside the hut were completed during the astral summer

2004–2005, while the development of methods to address

specific conservation problems at the site is well

underway. Far more must be done, however, before the

site is out of danger, which is why Shackleton’s Hut

remains on WMF’s 2006 Watch list. The need to increase

international support for preserving the hut is

underscored by the ambiguous legal status of the

explorers’ huts under the Antarctic Treaty and the

physical challenge of carrying out preservation work in

such an extreme environment.

1914–1916

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition set out from

London on August 1, 1914 with the goal of crossing the

Antarctic from a location near Vahsel Bay on the south

side of the Weddell Sea, reach the South Pole and then

continue to Ross Island on the opposite side of the

continent. The expedition's goal had to be abandoned

when the ship, Endurance, was beset by sea ice

short of its goal of Vahsel Bay. It was later crushed by

the pack ice.

The

ship's crew and the expedition personnel endured an epic

journey by sledge across the Weddell Sea pack and then

boat to Elephant Island. Upon arrival at Elephant Island

off the Antarctic Peninsula, they rebuilt one of their

small boats and Shackleton with five others set sail for

South Georgia to seek help. This remarkable journey in

the 6.7-meter boat James Caird through the Drake

Passage to South Georgia in the late Antarctic Fall

(April and May) is perhaps without rival. They landed on

the southern coast of South Georgia and then crossed the

spine of the island in an equally remarkable 36-hour

journey. The 22 men who remained on Elephant Island were

rescued by the Chilean ship Yelcho after three

other failed attempts on August 30, 1916 (22 months

after departing from South Georgia). Everyone from Endurance

survived.

What

was Shackleton's most difficult journey of exploration?

In 1914, in command of a party in the ship Endurance,

Shackleton set off to cross the Antarctic from one side

to the other, from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea. As

both Amundsen and Scott had reached the South Pole and

the Americans had reached the North

Pole, he saw this as

the last great challenge.

Although the expedition failed because

Shackleton did not reach the South Pole, in other ways

it was his biggest success. He triumphed over enormous

difficulties to bring his men safely home after the Endurance

was trapped and crushed by ice in the Weddell Sea.

To do so, he made an incredible journey to get help.

Shackleton and his men set sail in August 1914, just as

war was starting in Europe. On 19 January 1915, Endurance

became locked in the ice of the Weddell

Sea. Over

the course of the next nine months the ship was

gradually crushed, finally sinking on 27 October. It

proved impossible for the 28 men to drag their boats and

stores across the frozen sea so Shackleton camped on the

ice and drifted with it. When the ice began to break up

as it drifted north into warmer waters, the men launched

the three boats and, in dangerous conditions, managed to

reach Elephant Island. This rocky and barren island was

still more than 800 miles from the nearest inhabited

land with people who could help them.

They were cold and exhausted, and weak from the

hardships of the journey. They knew they would not be

found and could not all sail further. They were also

worried that their supplies of food would not last long.

There were seals and penguins to kill for food and fuel

but not many and they eventually had to rely on

collecting shellfish.

Sir Ernest Shackleton,

1874–1922

He decided to leave most of the party behind, while he

set out in a boat to reach South Georgia, the nearest

inhabited island, 800 miles away. He knew that he would

find help there, at the Norwegian whaling stations on

the north side.

No. He and five others left in the best of their ship's

boats, the James Caird. Although it was winter

and the Southern Ocean is the stormiest in the world,

they knew the plan was their best hope for the survival

of the whole party. When the six set sail, the rest of

the group were left behind to make camp on Elephant

Island. The James Caird was

just over 7 metres long and 2 metres wide.

Did

Shackleton make any changes to the boat before they set

sail?

Yes. The carpenter, 'Chippy' McNeish, made the bottom of

the boat stronger, and stretched a canvas deck over most

of it to give some shelter. The journey was extremely

dangerous. On many occasions, the six believed they were

about to sink in the terrifying conditions they

encountered, with waves which seemed as high as

mountains and violent storms. They were constantly wet

and cold and one of the biggest dangers they faced was

the weight of the ice collecting on the boat as the

sea-spray froze. Several times they risked their lives

hacking it off to prevent the boat capsizing. They also

had a real fear that their water would run out before

they made land. After 15 exhausting days at sea, they

finally sighted South Georgia.

They

found it very difficult to find a place to land their

boat safely, and were forced by gale, which nearly

wrecked them on the coast, to spend two more nights at

sea. Eventually, they managed to get into a cove in King

Haakon Bay on the south of the island. To their relief,

they found a stream with fresh water almost immediately.

They found a cliff

overhang where they could shelter and light a fire for

warmth.

Shackleton led, taking the tough seaman Tom

Crean and Frank Worsley, the expert navigator on the James

Caird, who also had mountaineering experience. The

journey involved a climb of nearly 3000 feet (914 metres).

They did not take a tent and could not rest for long

because they could easily freeze to death if they fell

asleep in the snow. Apart from short breaks they marched

continuously for 36 hours, covering some 40 miles over

mountainous and icy terrain.

They heard the steam-whistle of the Stromness

whaling station, signalling the start of another day's

work at 07.00. After scrambling down a final ridge, the

three men at last reached people who could help them.

They were all rescued. Those on Elephant Island had to

wait longer, until 30 August 1916, but were eventually

picked up by Shackleton on a Chilean navy tug. All the

men believed that their survival was due largely to his

tremendous leadership. Many would have believed it

impossible to bring all his men home with no lives lost.

Many of his men were to return immediately to the harsh

reality of the First World War. Tragically, after

surviving so many dangers with Shackleton, some were to

perish in it.

1921

Final expedition

In

1921, Shackleton set out on another Antarctic

expedition, but died of a heart attack on board his

ship, the Quest, while anchored off South Georgia Island

on January 5, 1922. His body was being returned to

England when his widow requested that the burial take

place on Grytviken, South Georgia Island instead.

Shackleton was buried there on March 5.

Nowadays,

the southern continent is shared between 27 nations that

have scientists based there. The things they study

include changes in climate and the destruction of the

ozone layer. For further information about the Antarctic

today visit the British

Antarctic Survey website.

Legacy

In

1994, the James Caird Society was set up to preserve the

memory of Shackleton's achievements. Its first Life

President was Shackleton's younger son, Edward

Shackleton.

Sir

Ernest Shackleton is the subject of Shackleton, a

two-part Channel 4 drama directed by Charles Sturridge

and starring Kenneth Branagh as the explorer. The same

story is related in greater detail in the book

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage, by Alfred

Lansing.

Shackleton's

grave, near the former whaling station at Grytviken on

South Georgia is frequently visited by tourists from

passing cruise ships. The

British Antarctic Survey's logistics vessel RRS Ernest

Shackleton (the replacement for RRS Bransfield) is named

in his honour.

THE

ENDURANCE

The name 'Endurance' has been applied to two ships of the Royal Navy, inspired by the 1912 ship used by Sir Ernest

Shakleton.

1912 SHIP

The Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton sailed for the Antarctic on the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. She was launched in 1912 from Sandefjord in Norway and was crushed by ice, causing her to sink, three years later in the Weddell Sea off Antarctica.

Design and construction

Designed by Aanderud Larsen, the Endurance was built at the Framnaes shipyard in Sandefjord, Norway and fully completed on December 17, 1912. She was built under the supervision of master wood shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen, who was renown for insisting that all men employed under him not just be skilled shipwrights, but also be experienced in seafaring aboard whaling or sealing ships. Every detail of her construction had been scrupulously planned to ensure maximum durability, for example every joint and every fitting cross-braced each other for maximum strength

She was launched on December 17, 1912 and was initially christened the Polaris (eponymous with Polaris, the North Star). She was 144 feet (43.9 m) long, with a 25 foot (7.6 m) beam and weighed 350 tons (356 metric tons). She was designed for polar conditions with a very sturdy construction, her sides were between 2 1/2 feet and 18 inches thick, with twice as many frames as normal and the frames being of double thickness. She was built of planks of oak and Norwegian fir up to two and one half feet thick, sheathed in greenheart, a notably strong and heavy wood. Her bow, where she would meet the ice head-on, had been given special attention. Each timber had been made from a single oak tree chosen for its shape so that is natural shape followed the curve of her design. When put together, these pieces had a thickness of 4 feet, 4 inches. Her keel members were four pieces of solid oak, one above the other, adding up to a thickness of 7 feet, 1 inch.

Of her three masts, the forward one was square-rigged, while the after two carried fore and aft sails, like a schooner. As well as sails, Endurance had a 350 hp (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine capable of driving her at speeds up to 10.2 knots (19 km/h).

By the time she was launched on December 17, 1912, Endurance was perhaps the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of the Fram, the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by Roald Amundsen. However, there was one major difference between both ships. The Fram was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her she would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the ice compressing around her. But since the Endurance was designed to operate in relatively loose pack ice she was not constructed so as to rise out of pressure to any great extent.

Ownership

She was built for Adrien de Gerlache and Lars Christensen. They intended to use her for polar cruises for tourists to hunt polar bears. Financial problems leading to de Gerlache pulling out of their partnership meant that Christensen was happy to sell the boat to Ernest Shackleton for GB£11,600 (approx US$67,000), less than cost. He is reported to have said he was happy to take the loss in order to further the plans of an explorer of Shackleton's stature. After Shackleton's purchase the ship was

re-christened Endurance after the Shackleton family motto "Fortitudine vincimus" (By endurance we conquer).

Final voyage

Shackleton sailed with Endurance from Plymouth, England on August 6, 1914 and set course for Buenos Aires, Argentina. This was Endurance's first major cruising since her completion and amounted to a shakedown cruise. The trip across the Atlantic took more than two months. Built for the ice, her hull was considered by many of its crew too rounded for the open ocean. On October 26, 1914 Endurance sailed from Buenos Aires to her last port of call, the Grytviken whaling station on the island of South Georgia off the southern tip of South America, where she arrived on November 5. She departed from Grytviken for her final voyage on December 5, 1914 towards the southern regions of the Weddell Sea.

The 25 man crew (and one stow away) were headed for Antarctica. The goal was to land on one side of Antarctica and send a 6 man dog sled team 3,000 kilometers across the continent to be the first to make a cross continental journey. As they journeyed South they joked with the young stowaway that if anything should happen he would be eaten first since there were no edible plants in Antarctica and only penguins, seals & walrus's during the summer.

Two days after leaving from South Georgia, Endurance encountered polar pack ice and progress slowed down. For weeks Endurance twisted and squirmed her way through the pack. Though slow, she kept moving but averaged less than 30 miles per day. By January 15, Endurance was within 200 miles of its destination, Vahsel Bay. However by the following day heavy pack ice was sighted in the morning and in the afternoon a blowing gale developed. Under these conditions it was soon evident progress could not be made, and Endurance took shelter under the lee of a large grounded berg. During the next two days Endurance dogged back and forth under the sheltering protection of the berg.

On January 18 the gale began to moderate and thus Endurance, one day short of her destination, set the topsail with the engine at slow. The pack had blown away. Progress was made slowly until hours later Endurance encountered the pack once more. It was decided to move forward and work through the pack, and at 5pm Endurance entered it. However it was noticed that this ice was different from what had been encountered before. The ship was soon engulfed by thick but soft ice floes. The ship floated in a soupy sea of mushy brash ice. The ship was beset. The gale now increased its intensity and kept blowing for another six days from a northerly direction towards land. By January 24, the wind had completely compressed the ice in the whole Weddell Sea against the land. The ice had packed snugly around Endurance. All that could be done was to wait for a southerly gale that would start pushing, decompressing and opening the ice in the other direction. Instead the days passed and the pack remained unchanged.

REDISCOVERY

OF ENDURANCE

BBC NEWS 9 MARCH -

ENDURANCE: 'FINEST WOODN SHIPWRECK I'VE EVER SEEN'

Endurance, the lost ship of Anglo-Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, has finally been identified on the floor of Antarctica's Weddell Sea. The vessel was crushed by sea-ice and sank on 21 November 1915, forcing Shackleton and his men to make a heroic escape on foot and in small boats.

Marine archaeologist Mensun Bound described the condition of Endurance to the BBC.

"Without any exaggeration this is the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen - by far.

It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation.

You can even see the ship's name - E N D U R A N C E - arced across its stern directly below the taffrail (a hand rail near the stern). And beneath, as bold as brass, is Polaris, the five-pointed star, after which the ship was originally named.

I tell you, you would have to be made of stone not to feel a bit squishy at the sight of that star and the name above.

And just under the tuck of the stern, laying in the silt is the source of all their troubles, the rudder itself. You will remember that it was when the rudder was torn to one side by the ice that the water came pouring in and it was game-over. It just sends shivers up your spine.

When you rise up over the stern, there is another surprise. There, in the well deck, is the ship's wheel with all its spokes showing, absolutely intact. And before it is the companionway (with the two leaves of its door wide open) leading down to the cabin deck. The famous Frank Hurley (expedition photographer) picture of Thomas Ord Lees (motor expert) about to go down into the ship was taken right there.

And beside the companion way, you can see a porthole that is Shackleton's cabin. At that moment, you really do feel the breath of the great man upon the back of your neck.

The funnel is still there, but not upright, lying semi-thwartships (almost at a right-angle to the keel), still with its steam whistle attached. Beside it is the engine room skylight. We could look down through it. I was hoping to see the cylinder heads of its triple-steam expansion engines, but couldn't quite make them out.

Near midships there is a boot, with another one, maybe its pair, in the debris field beside the wreck; also several plates and a cup.

When the mast fell, it crushed the ward room with the bridge deck above, but you can see the outline of the wardroom and beside it the galley and pantry. One wall of the galley is still standing with its two forward portholes intact.

On the weather deck, you can see the forward hold and skylight with the fo'c'sle deck (the upper-deck forward of the foremast) just beyond.

The fo'c'sle deck is damaged, for although the vessel went down keel first, she was down slightly at the bow so it was that part of the hull that first struck the seabed and so took the shock of impact.

The capstan is still visible on the fo'c'sle deck and beside it is one of the anchors. The other anchor broke free; it snakes out over the seabed.

The bow looks amazing. You can see its forward raking stem and the metal-shod cutwater that cleaved the ice.

The masts, spars, booms and gaffs are all down, just as in the final pictures of her taken by Frank Hurley. You can see the breaks in the masts just as in the photos. There is a tangle of ropes, blocks and deadeyes.

You can even see the holes that Shackleton's men cut in the decks to get through to the 'tween decks to salvage supplies, etc, using boat hooks. In particular, there was the hole they cut through the deck in order to get into "The Billabong", the cabin in "The Ritz" that had been used by Hurley, Leonard Hussey (meteorologist), James McIlroy (surgeon) and Alexander Macklin (surgeon), but which was used to store food supplies at the time the ship went down.

I had been hoping to find Orde Lees' bicycle, but that wasn't visible, nor were there any of the honey jars that Robert Clark (biologist) used to preserve his samples that I also hoped I might find.

The depth is 3,008m (9,868ft).

Endurance was found just over four nautical miles (7.5km) and roughly southward of Frank Worsley's famous sinking position (68°39'30" South; 52°26'30" West).

We found the wreck a hundred years to the day after Shackleton's funeral (5 March 1922). I don't usually go with this sort of stuff at all, but this one I found a bit spooky."

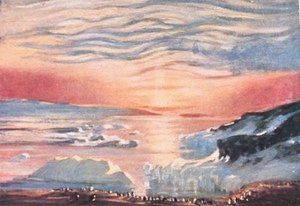

Sir

Ernest Shackleton and Endurance

Sunset

In: "The Heart of the Antarctic" Volume I

by Shackleton 1909

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-60654016

RETURN

TO BASECAMP

OR EXPLORE OUR

PREHISTORIC A-Z

|