A

vast expanse of ice and sub zero temperatures.

The Antarctic Treaty and related agreements, collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), regulate international relations with respect to Antarctica, Earth's only continent without a native human population. It was the first arms control agreement established during the Cold War, setting aside the continent as a scientific preserve, establishing freedom of scientific investigation, and banning military activity; for the purposes of the treaty system, Antarctica is defined as all the land and ice shelves south of 60°S latitude. Since September 2004, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, which implements the treaty system, is headquartered in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The main treaty was opened for signature on 1 December 1959, and officially entered into force on 23 June 1961. The original signatories were the 12 countries active in Antarctica during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–58: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These countries had established over 55 Antarctic research stations for the IGY, and the subsequent promulgation of the treaty was seen as a diplomatic expression of the operational and scientific cooperation that had been achieved. As of 2023, the treaty has 56 parties.

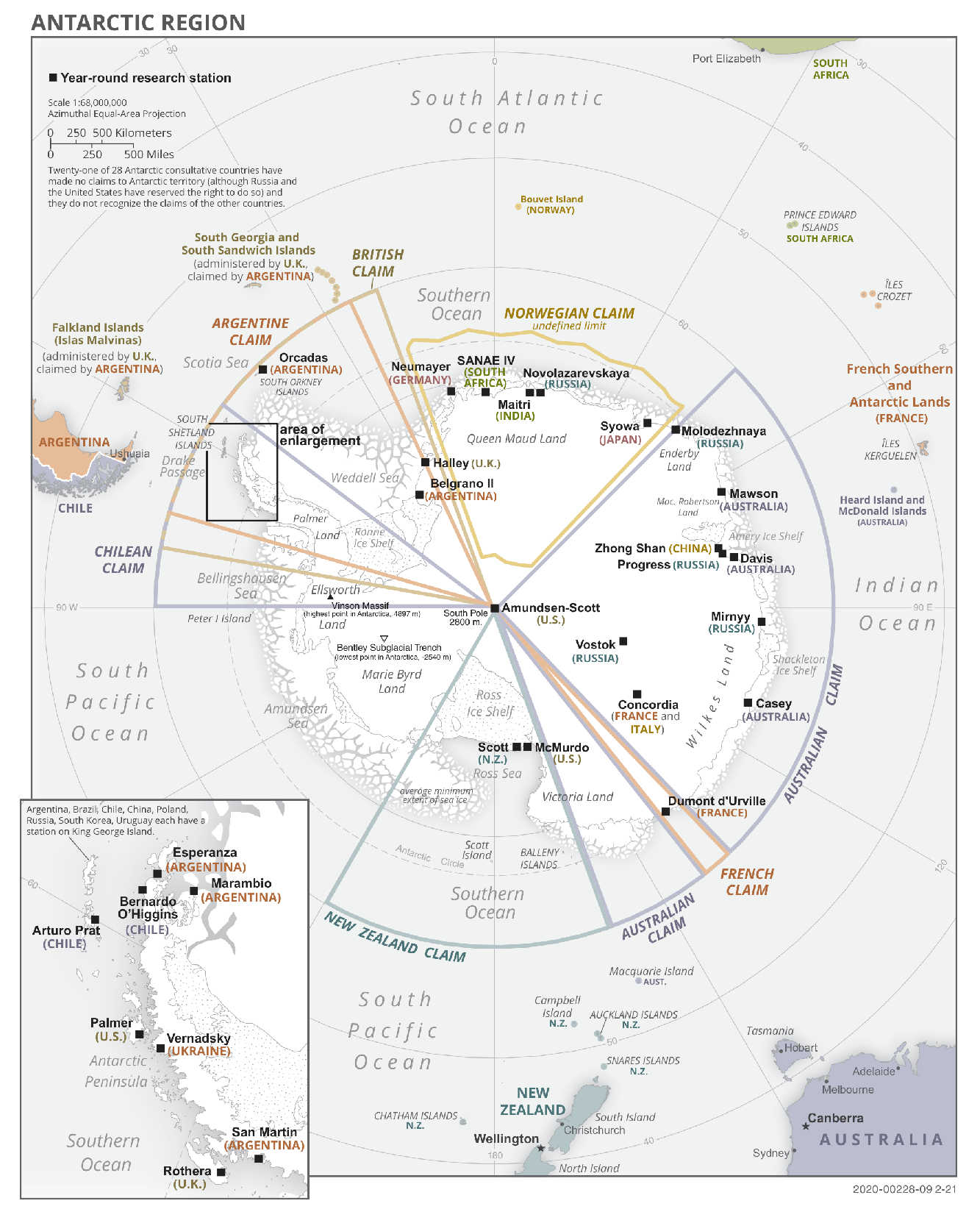

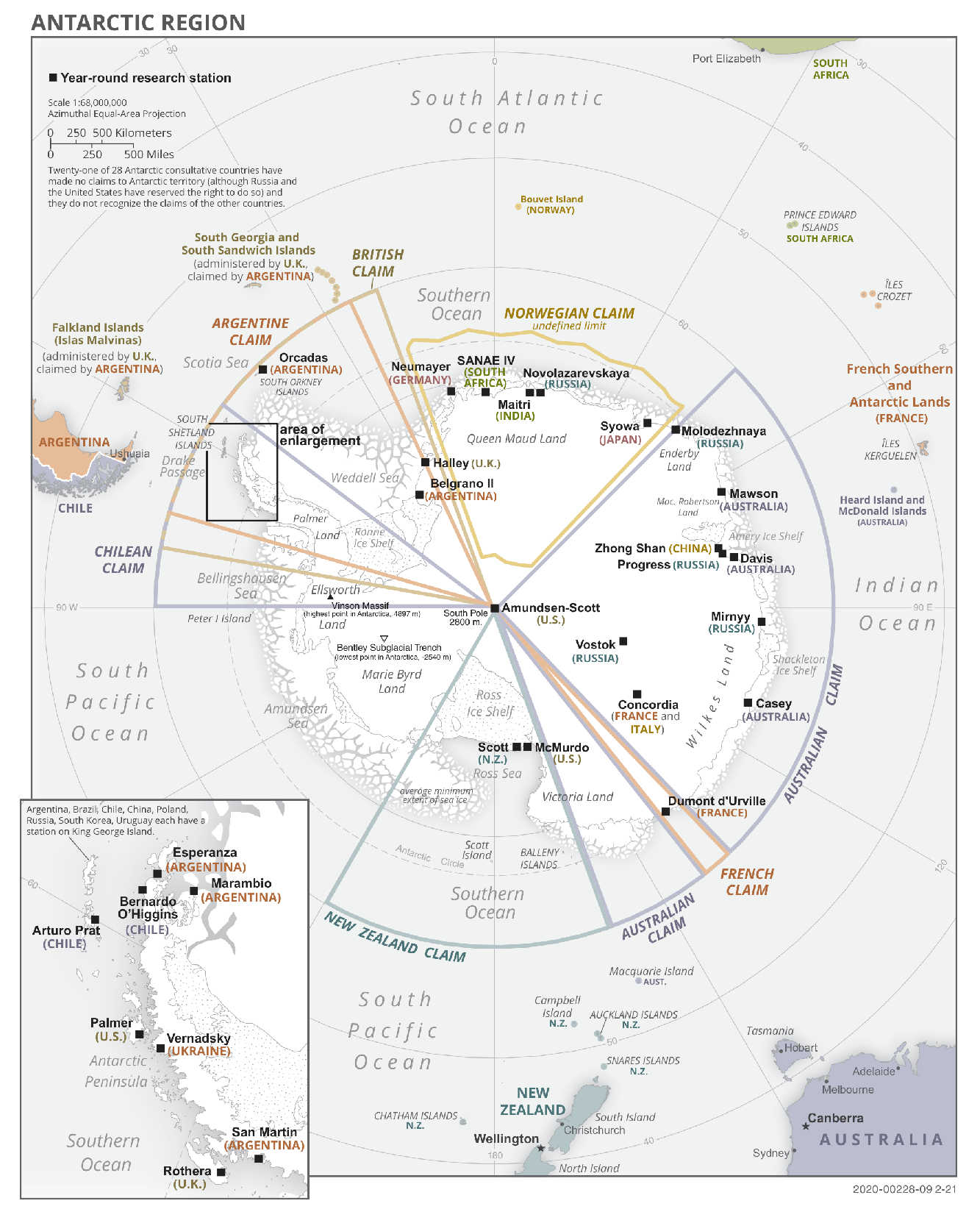

Antarctica currently has no permanent population and therefore it has no citizenship nor government. Personnel present on Antarctica at any time are always citizens or nationals of some sovereignty outside Antarctica, as there is no Antarctic sovereignty. The majority of Antarctica is claimed by one or more countries, but most countries do not explicitly recognize those claims. The area on the mainland between 90 degrees west and 150 degrees west is the only major land on Earth not claimed by any country. Until 2015 the interior of the Norwegian Sector, the extent of which had never been officially defined, was considered to be unclaimed. That year, Norway formally laid claim to the area between its Queen Maud Land and the South Pole.

Governments that are party to the Antarctic Treaty and its Protocol on Environmental Protection implement the articles of these agreements, and decisions taken under them, through national laws. These laws generally apply only to their own citizens, wherever they are in Antarctica, and serve to enforce the consensus decisions of the consultative parties: about which activities are acceptable, which areas require permits to enter, what processes of environmental impact assessment must precede activities, and so on. The Antarctic Treaty is often considered to represent an example of the common heritage of mankind principle. Something similar applies to the Moon - and space exploration.

As of 2023, there are 56 states party to the treaty, 29 of which, including all 12 original signatories to the treaty, have consultative (voting) status. The consultative members include the 7 countries that claim portions of Antarctica as their territory. The 49 non-claimant countries do not recognize the claims of others. 42 parties to the Antarctic Treaty have also ratified the "Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty". How this 'Treaty' came into being, is as a result of various claims of sovereignty, threatening peaceful interests, and scientific research.

THE 1940s

After World War

II, the U.S. considered establishing a claim in Antarctica. From 26 August 1946, and until the beginning of 1947, it carried out Operation Highjump, the largest military expeditionary force that the United States had ever sent to Antarctica, consisting of 13 ships, 4,700 men, and numerous aerial devices. Its goals were to train military personnel and to test material in conditions of extreme cold for a hypothetical war in the Antarctic.

On 2 September 1947, the quadrant of Antarctica in which the United States was interested (between 24° W and 90° W) was included as part of the security zone of the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, committing its members to defend it in case of external aggression.

In August 1948, the United States proposed that Antarctica be under the guardianship of the

United

Nations, as a trust territory administered by Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand. This idea was rejected by Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, and Norway. Before the rejection, on 28 August 1948, the United States proposed to the claimant countries some form of internationalization of Antarctica, and the United Kingdom supported this. Chile responded by presenting a plan to suspend all Antarctic claims for five to ten years while negotiating a final solution, but this did not find acceptance.

In 1950, the interest of the United States to keep the Soviet Union away from Antarctica was frustrated, when the Soviets informed the claimant states that they would not accept any Antarctic agreement in which they were not represented. The fear that the USSR would react by making a territorial claim, bringing the Cold War to

Antarctica. Fortunately, the United States made no claim.

INTERNATIONAL CONFLICTS

Various international conflicts motivated the creation of an agreement for the Antarctic.

Some incidents had occurred during the Second World War, and a new one occurred in Hope Bay on 1 February 1952, when the Argentine military fired warning shots at a group of Britons. The response of the United Kingdom was to send a warship that landed marines at the scene on 4 February. In 1949, Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom signed a Tripartite Naval Declaration committing not to send warships south of the 60th parallel south, which was renewed annually until 1961 when it was deemed unnecessary when the treaty entered into force. This tripartite declaration was signed after the tension generated when Argentina sent a fleet of eight warships to Antarctica in February 1948.

On 17 January 1953, Argentina reopened the Lieutenant Lasala refuge on Deception Island, leaving a sergeant and a corporal in the Argentine Navy. On 15 February, in the incident on Deception Island, 32 royal marines landed from the British frigate HMS Snipe armed with Sten machine guns, rifles, and tear gas capturing the two Argentine sailors. The Argentine refuge and a nearby uninhabited Chilean shelter were destroyed, and the Argentine sailors were delivered to a ship from that country on 18 February near South Georgia. A British detachment remained three months on the island while the frigate patrolled its waters until April.

On 4 May 1955, the United Kingdom filed two lawsuits, against Argentina and Chile respectively, before the International Court of Justice to declare the invalidity of the claims of the sovereignty of the two countries over Antarctic and sub-Antarctic areas. On 15 July 1955, the Chilean government rejected the jurisdiction of the court in that case, and on 1 August, the Argentine government also did so, so on 16 March 1956, the claims were closed.

In 1956 and 1958, India tried unsuccessfully to bring the Antarctic issue to the

United Nations General Assembly.

NEGOTIATION OF THE TREATY

Scientific bases increased international tension concerning Antarctica. The danger of the Cold War spreading to that continent caused the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, to convene an Antarctic Conference of the twelve countries active in Antarctica during the International Geophysical Year, to sign a treaty. In the first phase, representatives of the twelve nations met in Washington, who met in sixty sessions between June 1958 and October 1959 to define a basic negotiating framework. However, no consensus was reached on a preliminary draft. In the second phase, a conference at the highest diplomatic level was held from 15 October to 1 December 1959, when the Treaty was signed.

The Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959 by 12 nations and came into effect in the mid-1960s. The central ideas with full acceptance were the freedom of scientific research in Antarctica and the peaceful use of the continent. There was also a consensus for demilitarization and the maintenance of the status quo. The treaty prohibits nuclear testing, military operations, economic exploitation, and territorial claims in Antarctica. It is monitored through on-site inspections. The only permanent structures allowed are scientific research stations. The original signatory countries hold voting rights on Antarctic governance, with seven of them claiming portions of the continent and the remaining five being non-claimants. Other nations have joined as consultative members by conducting significant research in Antarctica. Non-consultative parties can also adhere to the treaty. In 1991-1992, the treaty was renegotiated by 33 nations, with the main change being the Madrid Protocol on Environmental Protection, which prohibited mining and oil exploration for 50 years.

The positions of the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand coincided in the establishment of an international administration for Antarctica, proposing that it should be within the framework of the United Nations. Australia and the United Kingdom expressed the need for inspections by observers, and the British also proposed the use of military personnel for logistical functions. Argentina proposed that all atomic explosions be banned in Antarctica, which caused a crisis that lasted until the last day of the conference, since the United States, along with other countries, intended to ban only those that were made without prior notice and without prior consultation. The support of the USSR and Chile for the Argentine proposal finally caused the United States to retract its opposition.

The signing of the treaty was the first arms control agreement that occurred in the framework of the Cold War, and the participating countries managed to avoid the internationalization of Antarctic sovereignty.

As of the year 2048, any of the consultative parties to the treaty may request the revision of the treaty and its entire normative system, with the approval of a relative majority.

A

startling discovery in the ice, sharp jaws protruding from a block of

solid ice.

BACKGROUND

The Antarctic continent is vast. It embraces the South Pole with permanent ice and snow. It is encircled by floating barriers of ice, stormy seas and appalling weather. Its great altitude chills the air to extremes, and its descent to sea level across a moving ice sheet generates the world’s strongest winds. The cycling seasons reveal the spectacular natural forces of our planet. The surrounding seas teem with wildlife. And just 2% of this continent is free of ice, allowing a small toe-hold for hardy animals and plants.

The weather and isolation dominate all who visit. The discovery and exploration of Antarctica was shaped by the continent’s remoteness and its extraordinarily inhospitable environment. These factors combined for centuries to keep humans away from all but the subantarctic islands and parts of the Southern Ocean where whaling and sealing took place. In human historic terms, the land exploration of Antarctica is recent, most of it being accomplished during the twentieth century.

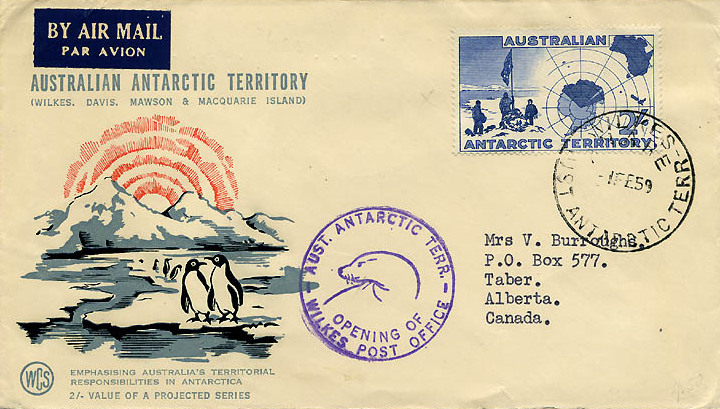

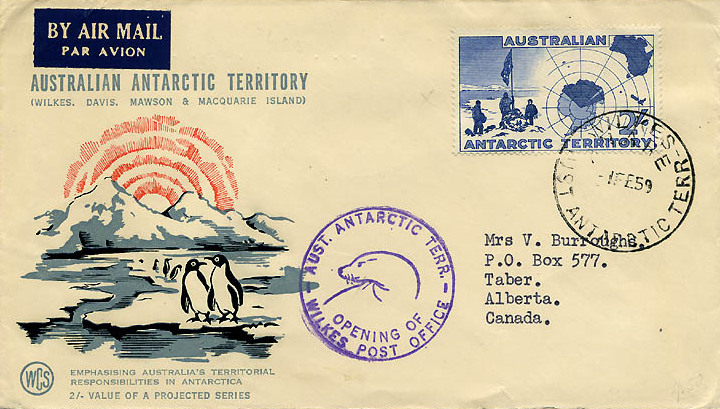

The improved technology and knowledge of the last 100 years allowed greater access to the continent, encouraging detailed surveying and research, and the gradual occupation of Antarctica by scientific stations. By mid-century, permanent stations were being established and planning was underway for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957-58, the first substantial multi-nation research program in Antarctica. By mid-century, territorial positions had also been asserted, but not agreed, creating a tension that threatened future scientific cooperation.

The IGY was recognised as pivotal to the scientific understanding of Antarctica. The twelve nations active in Antarctica, nine of which made territorial claims or reserved the right to do so, agreed that their political and legal differences should not interfere with the research program. The outstanding success of the IGY led these nations to agree that peaceful scientific cooperation in the Antarctic should continue indefinitely. Negotiation of such an agreement, the Antarctic Treaty, commenced immediately after the IGY.

SIGNING

OF THE ANTARCTIC TREATY

The Antarctic Treaty was signed in Washington on 1 December 1959 by the twelve nations that had been active during the IGY (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States and USSR). The Treaty, which applies to the area south of 60° South latitude, is surprisingly short, but remarkably effective. Through this agreement, the countries active in Antarctica consult on the uses of a whole continent, with a commitment that it should not become the scene or object of international discord. In its fourteen articles the Treaty:

- stipulates that Antarctica should be used exclusively for peaceful purposes, military activities, such as the establishment of military bases or weapons testing, are specifically prohibited;

- guarantees continued freedom to conduct scientific research, as enjoyed during the IGY;

- promotes international scientific cooperation including the exchange of research plans and personnel, and requires that results of research be made freely available;

- sets aside the potential for sovereignty disputes between Treaty parties by providing that no activities will enhance or diminish previously asserted positions with respect to territorial claims, provides that no new or enlarged claims can be made, and makes rules relating to jurisdiction;

- prohibits nuclear explosions and the disposal of radioactive waste;

- provides for inspection by observers, designated by any party, of ships, stations and equipment in Antarctica to ensure the observance of, and compliance with, the Treaty;

- requires parties to give advance notice of their expeditions; provides for the parties to meet periodically to discuss measures to further the objectives of the Treaty; and

- puts in place a dispute settlement procedure and a mechanism by which the Treaty can be modified.

The Treaty also provides that any member of the United Nations can accede to it. The Treaty now has 52 signatories, 28 are Consultative Parties on the basis of being original signatories or by conducting substantial research there. Membership continues to grow.

Since entering into force on 23 June 1961, the Treaty has been recognised as one of the most successful international agreements. Problematic differences over territorial claims have been effectively set aside and as a disarmament regime it has been outstandingly successful. The Treaty parties remain firmly committed to a system that is still effective in protecting their essential Antarctic interests. Science is proceeding unhindered.